There is a new wave of filmmaking beginning to emerge. Much of what makes it new is different emotional perspectives, and the cinematic way of presenting them.

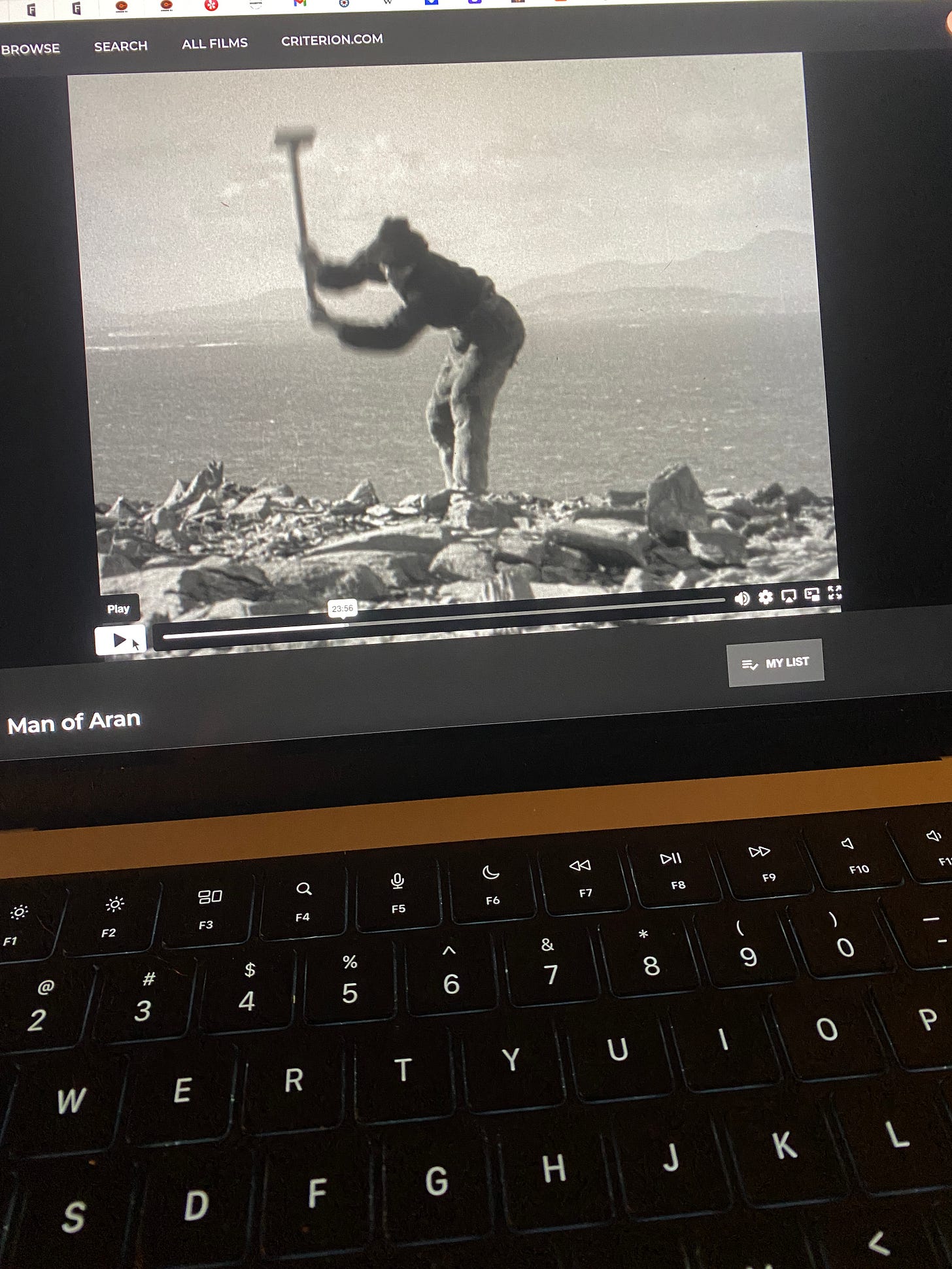

In William Friedkin’s 2013 memoir, “The Friedkin Connection,” he introduces the term “cinematic cubism.” Friedkin gives an example of breaking the expected and established editing format in Robert Flaherty’s film, MAN OF ARAN (1934).

“One sequence shows a man breaking a large rock with multiple blows of a sledgehammer. The man is seen bringing the hammer down right to left, but the close-up of the hammer hitting the rock is left to right; then the hammer comes down left to right, and we see in close-up the rick shattered, right to left. Shots of the man’s face are intercut, changing screen directions s well. These shots are cut together rapidly, and seem to draw our attention to the action more intently than if proper screen direction had been maintained. It was a kind of cinematic cubism.”

Film footage is traditionally shot while maintaining a 180 axis. Picture two people sitting across from each other at a table. You then seat yourself in the third seat, such that one person is on your right and the other is to your left. Now imagine you are the camera. Whether you’re shooting the person on your right or the person on your left, you stay on the “axis” on this side of both of them. What Friedkin is referencing in that MAN OF ARAN sequence, would mean you flipping from one side of the table to the other, and shooting the two people at the table from BOTH axes. When you cut footage like that together, it can seem chaotic because the viewer doesn’t know which side of the table the view is from.

Cubist painting is characterized as an object, person, or a scene disassembled and rearranged on the canvas. The subject is then represented from a multitude of perspectives all at once. This is a true representation of how our brains see objects. When one looks at a table, the fourth leg (and sometimes also the third) is not visible. And yet, our brain fills in those third and fourth legs to give us a complete picture in our mind of that table. We are not seeing the table at that moment from all sides, and yet in a cubist way, our brain has assembled the entire table in our mind.

And, so, cinematically we can arrange a film in a cubist manner to give a representation that is more so how our brain experiences situations. This “cinematic cubism” gives a more accurate emotional experience for the audience. As Friedkin continues about MAN OF ARAN, “These shots were cut together rapidly, and seem to draw our attention to the action more intently than if the proper screen direction had been maintained… to immerse the audience so deeply in a sequence…” There have been good examples of this in the past: Darren Aronofsky’s REQUIEM FOR A DREAM’s chaotic and hopeless drug sequences, Antonioni’s L’AVVENTURA’s existential seeking, Fellini’s 8 1/2’s inundating life experience, etc.

Now is the time to go beyond what we’ve seen in film, and more so apply this “cinematic cubism.” We can not only get closer in film to how humans experience the emotion of situations, but go beyond that even, and give a new, unexplored level of that experience. There are multiple ways to thrust into The New; this is a good one to step into.

Just know that I care about you all in these fires. I grew up there and pray for all of my friends and family and you all. Prayers up!

I'm curious how emotional cubism would work, how it would look, how it would inform the story, etc.